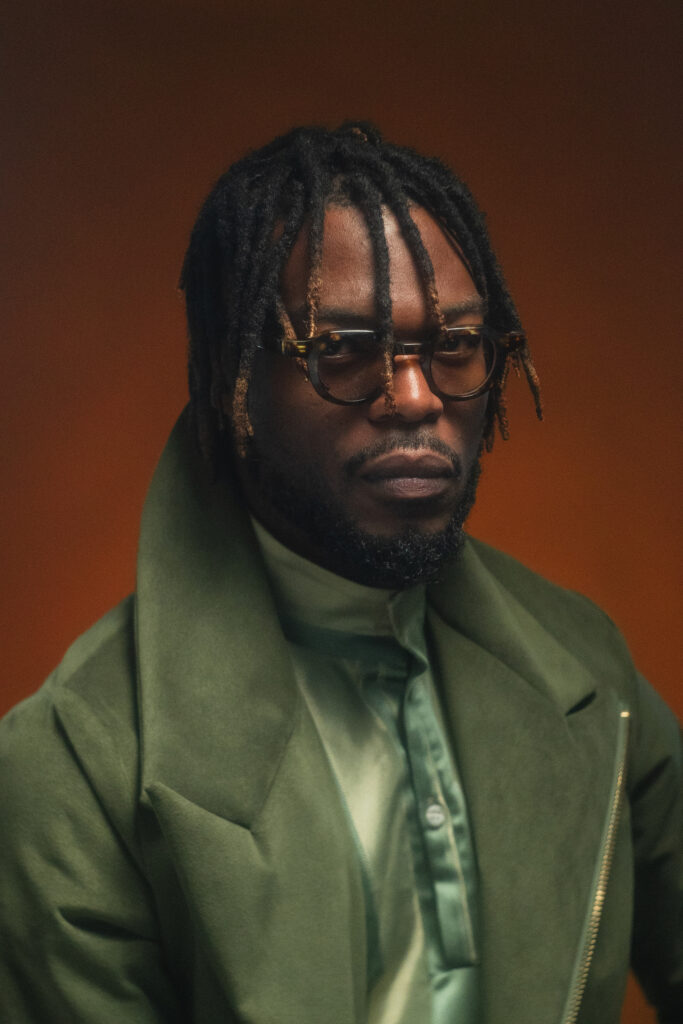

18 May A Visual Language: Discussing Film and Fashion with Walé Oyéjidé

BY KRISTAL SOTOMAYOR

Philadelphia-based artist Walé Oyéjidé is the definition of a multi-hyphenate–he is a talented fashion designer, filmmaker, speaker, photographer, musician, and lawyer. Oyéjidé utilizes his art to celebrate marginalized communities, with a focus on stories of African migration. Along with designer Sam Hubler, he founded the fashion brand Ikiré Jones, which blends classical design with African prints and has been featured in Coming 2 America and Black Panther.

Oyéjidé’s After Migration series uses film, photography, and fashion to depict beautiful migration stories. The short documentary film After Migration: Calabria demonstrates Oyéjidé’s signature style by creating beautiful portraits of migrants set in a quiet Italian village. Oyéjidé’s documentary feature directorial debut Bravo, Burkina! premiered at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. The film tells the tale of a young Burkinabé boy who migrates to Italy, yet is haunted by the memories of home as he deals with heartbreak and comes of age.

The cinéSPEAK Journal spoke with globally acclaimed artist Walé Oyéjidé about his innovative artmaking and the process of producing Bravo, Burkina!.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

cinéSPEAK: Bravo, Burkina! is a powerful story about belonging and reimagining immigrant stories. How did you get started on the film? Where did the idea come from?

Walé Oyéjidé: It’s the first film of a trilogy of feature films about migrants. The idea is to tell intentionally beautiful stories about migrants around the globe in a way that does not harp on or lean on the trauma of the migration experience, but instead shows the nuance that these individuals have. It shows the hopes and the dreams and, importantly, as you can see in Bravo, it shows the chasm that’s left behind when anyone leaves. It’s asking us to reckon with the people in the places that we leave behind, understanding that they continue without us, and what is impacted by us not being there. It seeks to ask questions as opposed to answering. Bravo was designed to be very much a fable or an allegory. It’s almost like the idea that you could tell a little kid the story, or you could tell a very sophisticated person who [knows] about immigration issues, the same story. They will take different things from it. And so this specific film is intended to become an introduction for my ethos and aesthetic and really my mission, which is ultimately seeking to promote cultural acceptance through the use of storytelling and gripping, impactful, stunning imagery.

cinéSPEAK: Where are you at with the other films in the trilogy?

WO: Film two has been written and we’re working on development now. I have ideas for the others, but it’s one step at a time. I think the first one was really a fantastic privilege because the hope is that people like Bravo, Burkina!. And the hope is that if people like what they see there, then it’s like, well, we got a lot more cooking that’s much more ambitious, that’s still essentially the same ethos, the same mission, the same vibe, but just with a lot more.

cinéSPEAK: Congratulations! I’ve seen that African migrant stories are very important to your work. You made a series in 2016 called After Migration that follows asylum seekers in Italy styled in your fashion designs. Why are you kind of driven to tell these stories?

WO: In 2016, I was invited to Italy as a designer to present a fashion show [at] the height of the refugee crisis. It’s when we were really seeing these images in newspapers of various asylum seekers washing up on the shores and I found it difficult to go and celebrate my work without addressing the societal issues that I was passionate about. From that moment, it was the idea of, “What if you as an artist use your work to speak to the issues around you?” So that’s when we began casting migrants and asylum seekers first to model for us and then eventually what became After Migration: Calabria, which was the short documentary. That documentary really was fantastic because that was my first film and it gave me the language of what it is that one can do with one’s art. That film was an exercise. You can use your clothing to literally, in this case, clothe these people and [depict] them in a way that [people who] might be biased towards them have never seen them. And perhaps more importantly, you can make them see themselves in a beautiful way that they’re not accustomed to seeing. What happens when the outsider becomes the figure that you want to become? Using beauty as a weapon, using the tools of beauty to sneak in messages of acceptance, messages of inclusivity and using the tools of beauty to uplift persons who have not traditionally been seen as beautiful. After Migration gave me a methodology and a visual language. And now that I have this tool set, that becomes further refined in Bravo, Burkina! where we again did the wardrobe. And so you’re again seeing the tools of fashion being used to illustrate a wonderful universal story.

cinéSPEAK: The designs for your label Ikiré Jones are so beautiful and have been seen in Black Panther and Coming 2 America. One can see your Nigerian American heritage in your artistry and your storytelling. Could you talk more about your heritage, being first generation, and how that’s impacted your storytelling?

WO: I think literally every artist in the world is trying to fix the problems from their youth and fix the anxieties that they had, or are dealing with that in some way. I think very much about the idea of me having the privilege to immigrate to this country but also how difficult that is. I came in my early teens, as a child. Just by nature, coming to a new place there are tons of insecurities that come with that. It’s hard enough to be a teenager but it’s harder when you’re coming to a place when you’re not one of many. What that does is you try to flatten your identity, you kind of blend in as human nature. But as you get older you realize the things that make you special, that’s what makes you powerful. As I mature as an artist and as my voice [grows], a lot of my work is reaching back to the thing that I brought with me, the culture and seeing if there are ways to inject that into this space. It’s the idea [that] if you get invited to a dinner, you bring your own meal, and by everybody bringing their own contributions, culturally, we have a much better feast for everybody.

A lot of my work is really about injecting my personal identity, but also being aware that my identity is shaped by everywhere. I’m not just Nigerian; I’m also very, very American. But I’m also a globalist. I’ve lived around the world. I think if you look at Ikiré Jones as an example, or you look at Bravo, Burkina!, you see influences from everywhere: you’re hearing the score, that it’s very wonderful European string arrangements, but they also have West African string chords, on top of the clothing that has these bold African colors but then the silhouettes are also European. You’re hearing Italian being spoken, you’re hearing Moore, which is the West African language being spoken. It’s a huge melting pot. That’s actually why it’s interesting to me. It’s quite special to me because it’s a film I haven’t seen before and I think that’s because it’s drawing upon the many cultural influences of myself, but also for my collaborators.

cinéSPEAK: I wanted to ask you about the process that you went through to make the film. You talked about collaborations impacting your work. How did your connection to Philadelphia inform your storytelling? For example, I did see award-winning Philly-based filmmaker Sosena Solomon was one of the editors on Bravo, Burkina!.

WO: Sosena is fantastic. Philly was great because this is a city that is not oftentimes well resourced, particularly when it comes to film. We just assume that we just ain’t got it. I gotta shout out All Ages Productions and Independent Public Media Foundation (IPMF). Both of them were incredibly helpful in getting this made. We filmed the film, but when I came home I needed to edit and All Ages gave us an editing booth and helped facilitate Sosena and I cutting the film together. We cut the film in like a month and then IPMF provided finishing funds. When the film got into Sundance, it was like, the more money, more problems. We’d already gotten [the] film into Sundance, [so we had] to finish the film. So things like post-production, sound mixing, which was done here by Dragonfly Audio in Philadelphia, and coloring which was done by Company Three in New York. All these things cost money. This is where IPMF came in to help offer a little bit of assistance. We don’t often trumpet our own very much. There are assets here within the community, and I think it’s a question of digging around and finding like-minded people who believe in the work of artists and believe in the mission. This is not a Philadelphia story but I believe it’s a universal story. People of any walk of life, including Philadelphians, can find something. I think there’s something to be said for the community here being really tight and understanding that there’s great work being done, even though we’re not seen as being on the same level. We don’t trumpet it as loudly as you would in places like New York or London.

*Featured Image: Still from Bravo, Burkina! Courtesy of Walé Oyéjidé.

Bravo, Burkina! will screen at the 2023 Philadelphia Film Festival coming in October.

Kristal Sotomayor is a bilingual Latinx freelance journalist, documentary filmmaker, and festival programmer based in Philadelphia. They serve as the Editor-In-Chief of the cinéSPEAK Journal and Programmer for True/False Film Fest, SFFILM, and Frameline.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.