12 Oct Summer of Soul and The Sound of Resistance

BY JOHN MORRISON

For as long as I can remember, the African/Black American cultural festival has been an institution in my life. Both of my parents are from North Philly–the Nicetown-Tioga section to be specific. Some of my earliest memories are of summertime block parties in the neighborhood that were full of dancing, barbeque, laughter, and joy. One particularly powerful memory of those days is of the storefront cultural space on Westmoreland street that would bring djembe drummers, masked stilt-walkers, dancers, and other African cultural productions to the gatherings. Witnessing all of this unfamiliar music and art was very exciting to me as a kid, and it made an indelible impact on my viewpoint of the world and my own understanding of what it meant to be Black in America. Without many tangible, physical connections to Africa and the diaspora, these cultural festivals have provided Black Americans with a chance to reconnect the cultural links that the transatlantic slave trade sought to sever permenantly. By opening space for Black folks to commune with each other and celebrate our history and culture, these festivals have been an important tool in Black America’s long and arduous effort to develop a deeper, more whole sense of self.

In the summer of 1969, the question of Black revolution was not only “on the table” in a rhetorical sense, it was a question that lived in the minds, hearts, and actions of many Black people throughout the nation. Nearly one year before, on April 4th, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King was struck down by an assassin’s bullet while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. Dr. King had come to Memphis to show his support in solidarity with the city’s striking sanitation workers. The assassination of Dr. King let loose a firestorm of accumulated frustration and rage that had been boiling inside Black America for generations. For many, Dr. King represented the last hope for American redemption. Dr. King and the nonviolent vision that he professed and lived by offered White America a roadmap to overcome the virulent racism that rotted this nation to the core, peacefully. By murdering the country’s most passionate and visionary exponent of nonviolence, it was clear that White America had opted for the “other” road and Black people across the country would respond in kind. In the weeks and months following Dr. King’s death, violent uprisings would occur in 100 American cities resulting in an estimated 43 deaths and thousands of injuries. In a direct response to mounting political pressure and an attempt to quell the civil unrest, the federal government passed the Civil Rights Act of 1968 which contained the Fair Housing Act. City and state governments as well as private entities would also take action, pumping money into everything from jobs training initiatives to cultural programming. In the summer of 1969, New York’s Parks, Recreation and Cultural Affairs Division would partner with a handful of corporate entities to sponsor The Harlem Cultural Festival, a massive free festival series hosted at Mount Morris Park (now known as Marcus Garvey Park) in Harlem. The late 1960s and 70s not only stirred up the rage and frustration that Black America felt, but this era also inspired the wholesale embrace of traditional African cultural mores. Public events like the Harlem Cultural Festival as well as Odunde in Philadelphia and the Watts Summer Festival in Los Angeles were and are important parts of the Black resistance struggle as they’ve created space for Black folks to openly celebrate African diasporic culture.

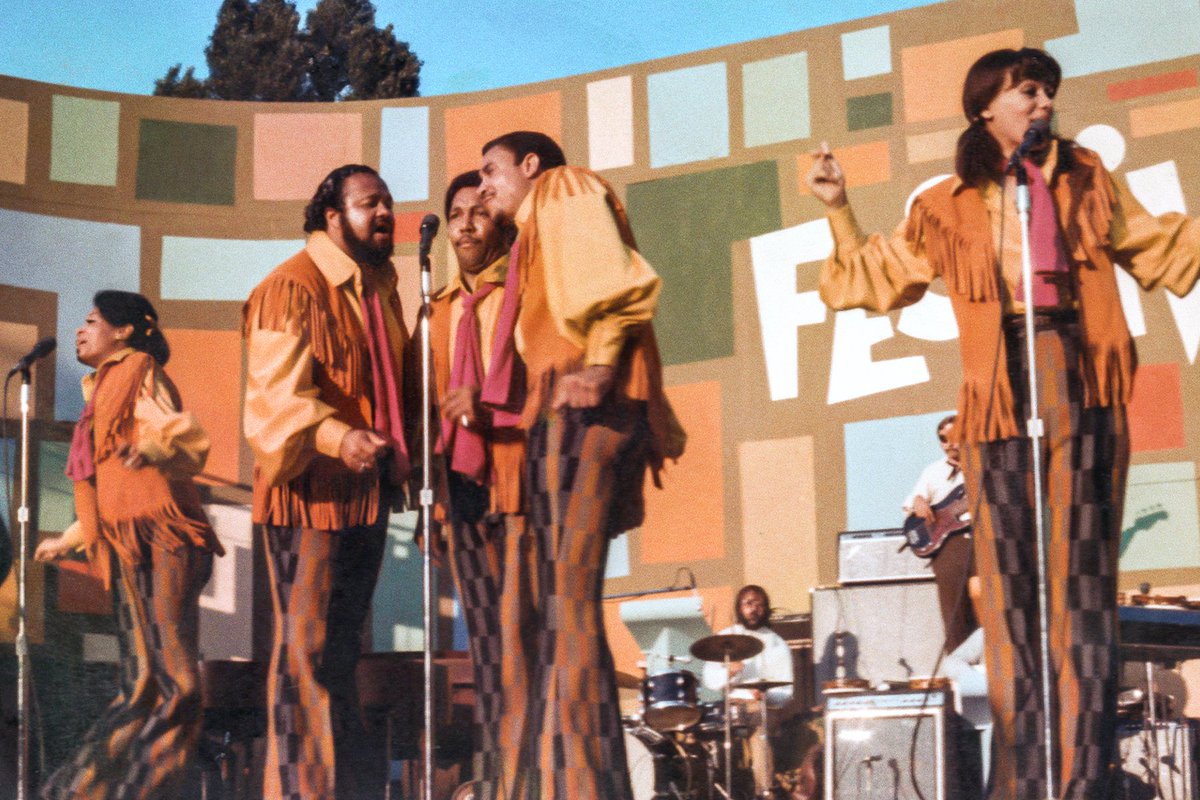

Summer Of Soul (…Or When The Revolution Could Not Be Televised) is the directorial debut of The Roots drummer and cultural polyglot Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson. Combining beautiful footage of the festival that was shot for broadcast by TV producer Hal Tulchin and preserved by film archivist Joe Lauro with revealing talking head interviews, Summer Of Soul captures the rich and turbulent spirit of the late 60s Black power era. The festival brought together a staggering lineup of Black creative talent with performances from Nina Simone, Stevie Wonder, The 5th Dimension, Mongo Santamaria, Sly & The Family Stone, Sonny Sharrock, The Chambers Brothers, Ray Barreto, Moms Mabley, The Staple Singers, B.B. King, Mahalia Jackson, Roy Ayers, The Edwin Hawkins Singers, Willie Tyler and Lester, Abbey Lincoln and Max Roach, Babatunde Olatunji, Hugh Masekela, Herbie Mann, Gladys Knight & The Pips, David Ruffin, and more. With interviews from festival attendees and performers as well as commentary provided by figures like Al Sharpton, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Greg Tate, and others, Summer Of Soul not only gives context to the performances that happened that summer, but the film also deftly deals with the many complex sociopolitical dynamics that were happening around the festival.

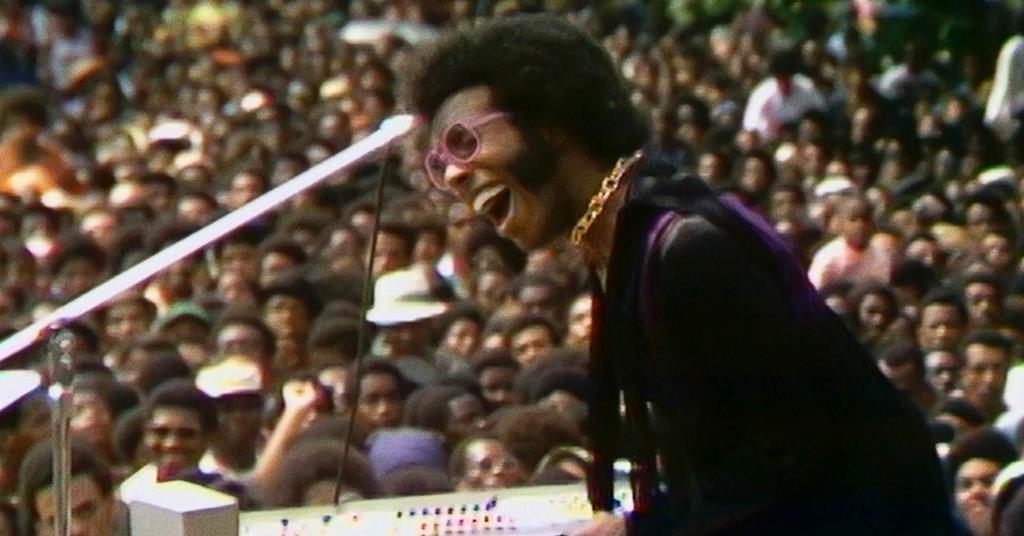

The film opens with Stevie Wonder performing a loose and funky version of the Isley Brothers’ “It’s Your Thing” in the rain. At first glance it is striking how good this footage looks after remaining unseen by the general public for over five decades. As Stevie warms up the crowd, the camera is cast over the crowd of tens of thousands of Black folks smiling, dancing and grooving beautifully. From here we get some important historical context on the role that Harlem as a neighborhood played as host to the festival as well as its role as the cultural and intellectual heartbeat of Black America. “Harlem was heaven to us. It was a place where I was safe, happy and made lifelong friends,” festival attendee Dorinda Drake recalls as Mississippi psychedelic-soul pioneers The Chambers Brothers perform their tune “Uptown.” As Drake recounts sweet memories of growing up in Harlem and its rich cultural life, the film’s archival broadcast footage takes us there.

Piggybacking off of this section on Harlem in particular, Summer Of Soul casts its focus outward, speaking to the state of Black America in 1969 and the revolutionary mood that was stirring in our communities at the time. From here, B.B. King, introduced by the Harlem Cultural Festival’s host and promoter Tony Lawrence as “the world’s greatest blues singer,” launches into “Why I Sing The Blues,” a song that takes us to the heart of Black American music and sums up the past, present and future of Black life in America:

“Everybody want to know why I sing the blues.

You know I’ve been around a long time.

People, I have really paid my dues.

I first got the blues when they brought me over on a ship.

There was men standing over me and a lot more with a whip.

I’ve laid in the ghetto flats cold and numb.

I’ve heard the rats tell the bedbugs to give the roaches some”

One remarkable aspect of Summer Of Soul is its pacing and structure. With the story and corresponding performances touching on the sacred gospel sound of Edwin Hawkins, Professor Herman Stevens & The Voices Of Faith, Clara Walker & The Gospel Redeemers, The Staple Singers, and Mahalia Jackson, the film unfolds like the history of Black music itself, illustrating the music’s importance to both the political and spiritual tenor of the people. In one clip, Greg Tate says, “There’s something very specific about what happened in Black America where I think the only place we could be fully expressive was in music, was in these church rituals.” Al Sharpton expounds on this sentiment, stating, “Gospel was more than religious. Gospel was the therapy for the stress and pressure of being Black in America.”

Performances from Mongo Santamaria and Ray Baretto as well as interviews with Denise Oliver-Velez, Sheila E. and Lin-Manuel Miranda help reinforce the Afro-Latinx presence at the festival, in Harlem as a neighborhood and in African diasporic culture in general. The late 60s had not only stirred up Black America’s rage; this era was also defined by an all-encompassing embrace and celebration of Blackness and African diasporic values and cultural mores. Summer Of Soul illustrates this beautifully. Concluding with rousing performances of “Are You Ready Black People?” from Nina Simone, Sly & The Family Stone’s “Higher,” and Musa Jackson’s heartfelt recollections of the beauty of the festival, Summer Of Soul is a healing and uplifting filmic experience. The brilliance and star power and virtuosity of the performers aside, the film soars on the strength of its loving and adept handling of Black history and culture.

Where to watch: Hulu

John Morrison is a writer, DJ, and radio host from Philadelphia. His work has appeared in NPR Music, Red Bull Music Academy, Bandcamp Daily, and more.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.